Yuri Tsivian: Kino-Pravda No. 10, 11, 13, 14 (1922)

The new cult of speed and skill (two things considered lacking in "old" Russia) explains why the bulk of Kino-Pravda No. 10 is taken up by the All-Russia Olympiad. Note the editing of the shots showing javelin-throwing and pole-vaulting. It appears to be experimenting with what Vertov's writings call "a precise study of movement." Preparation – launch – flight – fall, one shot per each phase of the trajectory. Clarity and precision were as important as skill and speed. Vertov's editing style here becomes athletic.

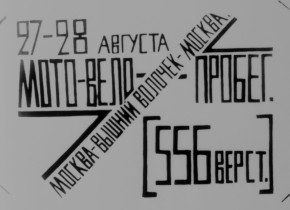

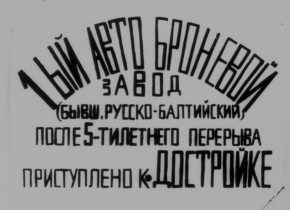

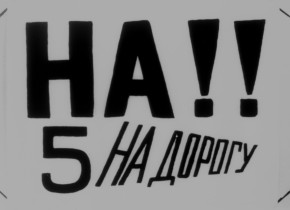

Clarity and precision were also qualities cultivated by Constructivist art – the recently-born Soviet art movement which waved farewell to easel painting and welcomed engineering and design. Vertov was friends with the Constructivist artist Aleksandr Rodchenko, who agreed to design the titles for Vertov's films. According to documents, their collaboration began with Kino-Pravda No. 7 (July 1922), but it is hard to confirm since only a fragment of issue 7 exists. But the proudly practical, deliberately uncomplicated, brick-like (or block-like, blochny) Constructivist lettering which we see in Kino-Pravda No. 10 (September 1922) is definitely by Rodchenko.

Vertov never thought of his group or his films as Kino-Constructivist, but many did, including the Constructivist theorist and designer Aleksei Gan, whose review of Kino-Pravda No. 10 (in Kino-fot, 1922, No. 4) is worth quoting: "The 10th Kino-Pravda is valuable not only for the abundance of material; its value lies in the rhythm and tempo to which the film conforms, from the first shot to the last.

The international festival of the union of youth, and assembling a car, and restoring a factory – in a word, people, machines, and the material environment – all this has been presented by means proper to cinema as such, without any touches of conventional film aesthetics. In it American montage is just a means for making it possible to construct sequences, shots, and individual scenes. The newsreel ceases to be illustrative material reflecting this or that place in our many-sided contemporary life, and becomes contemporary life as such, outside of territories, time, or individual significance. The whole tenth issue has screen-high intertitles. And here too Vertov has overcome the worn-out technique of horizontal writing. It is clear that words must be constructed on screen in a different way. I cannot call this attempt fully realized, but a word has been spoken. Now it will be shameful to write 'in the old way'. I and all young filmmakers await the eleventh issue of Kino-Pravda."

Kino-Pravda No. 11 is more like your regular newsreel, complete with delegations, diplomats, and speakers (be careful not to miss an astonishing close-up of a carafe of water sitting on the podium of one of the speakers, with the whole crowd of listeners and a nearby church reflected in it, upside down).

Kino-Pravda No. 12 is the only issue that has not been found (although Aleksandr Deriabin assures me that he knows where to look for it, and knowing him, he knows).

Kino-Pravda No. 13 is a magnum opus. Originally 900 metres long, this issue was timed to be released for the fifth anniversary of the October Revolution, and had a separate title: "Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow. A Film Poem Dedicated to the October Celebrations." A celebration like all celebrations: Trotsky, speeches, demonstrations – and suddenly, a jewel: an extreme close-up of someone's mouth shouting "Hurray!" The reason why Vertov called this film A Film Poem becomes clear in the second – Yesterday – reel. Its purpose is a replay, in retrospect, of the 5 years that have elapsed between 1917 and 1922. Its material is found-footage, often from Vertov's own earlier films, mostly from the Civil War years. A large part of this footage, as you may recall from the selection of Kino-Week newsreel shown earlier, was about burials of heroes. What Vertov does here is to take various funerals, which took place at different times in different towns, and piece them together so that the result looks like a single funeral – some kind of simultaneous, over-arching funeral in which the whole country is participating. This is how Aleksei Gan describes the effect in his 1922 review (Kino-Fot, no. 5, 10 December 1922, pp.6–7): "The graves in Astrakhan, the spades burying the bodies of our fallen heroes in Kronstadt, the banners lowered at the moment of burial in Minsk. We take off our hats. The Muscovites do the same on the embankment of the Moscow River."

And this is how Vertov theorized it in his 1923 manifesto "Kinocs: A Revolution" (as translated in Annette Michaelson, ed., Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov, 1984, pp.16–18): "You're walking down a Chicago street in 1922, but I make you greet Comrade Volodarskii walking down a Petrograd street in 1918, and he returns your greeting. Another example: the coffins of national heroes are lowered into the grave (shot in Astrakhan in 1918); the grave is filled in (Kronstadt, 1921); cannon salute (Petrograd, 1920); memorial service, hats are removed (Moscow, 1922) – such things go together, even with thankless footage not specifically shot for this purpose (cf. Kino-Pravda No. 14) ... Freed from the rule of 16–17 frames per second, free of the limits of time and space, I put together any given points in the universe, no matter where I've recorded them. My path leads to the creation of a fresh perception of the world. I decipher in a new way a world unknown to us."

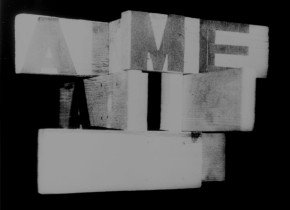

I want to announce Kino-Pravda No. 14 as a barker might a fairground show: Make sure you are not late, or you will miss Aleksandr Rodchenko's mobile installations, the likes of which you have never seen, either in film history or in the history of art! Their purpose is as unusual as their look: these installations were made to hold 3-dimensional intertitles, which are read as they roll. Imagine a wooden construction which looks like a crude kitchen stool, but cannot be used as one since its legs are facing in all different directions. This construction is suspended in mid-air by seemingly invisible means and revolves around a vertical axis; as it does so, it displays words and phrases written on its different facets.

Why did Vertov want intertitles for this film to rotate in space? It turns out that these mobile Constructivist affairs (anything but round) were meant to evoke a globe: as the first of them makes a complete turn the phrase that emerges is "On one side ...". What exactly is "on one side" becomes clear in the next shot. It displays another – different – wooden construction, which rotates the same way, only now a word, not a phrase, is revealed to us, letter by letter: A – turn – ME – turn – RI – turn – C ... – and when the circle is complete, the first A returns. We are then shown the Land of Capital, its skyscrapers and restaurants, seas of bowler hats. When Vertov wants us to return to what is going on at the same time in Russia, another rotating structure (this one resembling a wooden ancestor of modern radar) unfurls the phrase "On the other side ... ". Little wonder that the credits for Kino-Pravda No. 14 proudly call this film "Dziga Vertov's experiment in newsreel," and name Rodchenko as the maker of its intertitles.

From: Yuri Tsivian, Catalogue "Le Giornate del Cinema Muto," Sacile/Pordenone 2004